---

title: IPCV Practical - Filtering and segmentation of 3D CT thoracic image

---

# IPCV Practical - Filtering and segmentation of 3D CT thoracic image

> Course [Digital geometry processing](https://codimd.math.cnrs.fr/s/dc2zU_Cui) (<a href="ipcv.eu"> Master IPCV </a>)

> [name=Jacques-Olivier Lachaud][time=Nov 2025][color=#907bf7]

###### tags: `DGtal` `3d` `filtering` `segmentation` `CT image`

[TOC]

The objective of this practical is to filter a 3D Computed Tomography image of a thorax and to segment the vascular tree of the lungs. This will teach you how to load/save 3d images, how to extract digital surfaces, how to apply morphological filters, how to compute connected components and how to find the interior of surfaces.

Images are samples from the [Parse2022 Grand challenge](https://parse2022.grand-challenge.org/Parse2022/), a challenge where participants were asked to design the best possible methods to extract the pulmonary artery system out of 3D CT images [^1][^2]. Some input images are given in `data` subdirectory and called `PA*-img.vol` and `PA*-img-low.vol`, the later being downsampled versions for making easier your tests, especially if your computer is not so powerful. Examples of labelled images are also given as `PA*-lbl.vol` and `PA*-lbl-low.vol`. We won't be able to obtain such good segmentations (those were obtained by manual annotation), but we will be able to obtain the pulmonary vascular system.

## Getting started

In the DGtal-DGMM `practical-filtering` repository, have a look to the `vol-filter.cpp` file. If you are in your build repository, it should compile as is and is executed simply in the command line with

```

./vol-filter -i ../data/PA05-img-low.vol

```

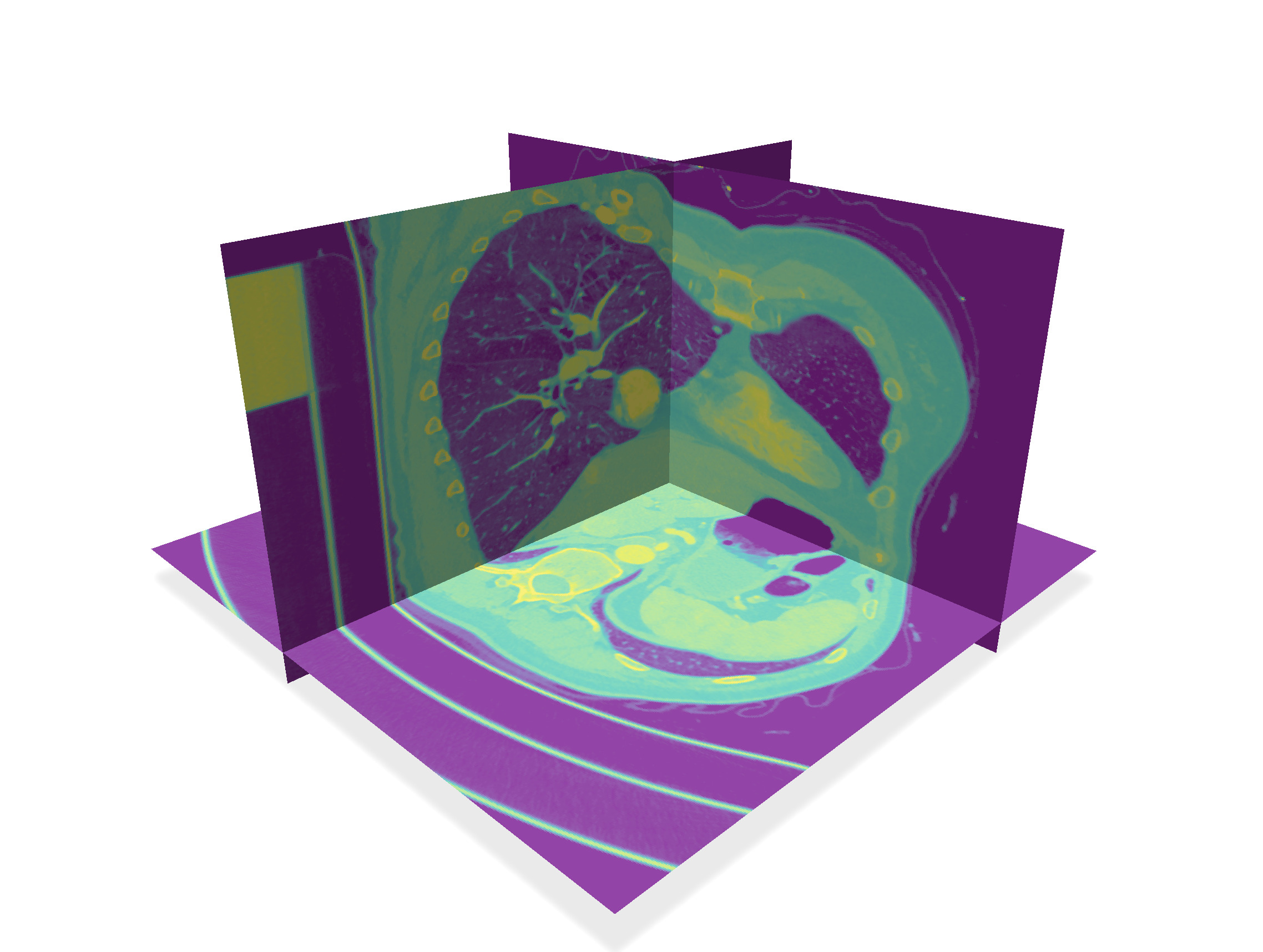

Similarly to the `volViewer` program, it will display the input 3d image, provides you with image slicers to "see" the image, as well as a way to extract the digital surface that is the boundary of the thresholded image. For instance, you can visualize the volume `PA16-img.vol` like this:

| Slices | Threshold 80 | Threshold 200 |

| -------- | -------- | -------- |

|  |  |  |

## Global overview of the segmentation method

:::info

Playing around with `volViewer` on these images, we see that we cannot simply threshold the image to get the pulmonary artery system. For instance bones and parts of the mechanical support, even sometimes a part of the bra are bright parts of the image.

Fortunately the lungs and their connection to the trachea are dark inside a brighter component (see threshold 80 above).

:::

In this practical, we will follow these steps to extract the pulmonary vascular system

1. **Morphological filtering** As a starter, we write two classical morphological 3d filters, dilation and erosion.

2. **Extract connected components of digital surfaces** The digital surface that is the boundary of a thresholded image is generally not connected. We split it into its connected components, and sort them by decreasing size.

3. **Fill inside lungs** At a threshold between 50-90 (we took 80 here), the largest connected component is precisely the boundary of the lungs and trachea. We design an algorithm that extracts the interior voxels of a given surface, in order to get a binary image representing the pulmonary system.

4. **Select lungs from original image** We eliminate all the complex bronchial and artery system within the lungs using the morphological filters. Then we use this binary image of lungs to select them in the original image, this removing all the other bright parts of the image.

5. **Extract boundaries of vascular system** We can now threshold the resulting image (approx. 150) to get the pulmonary vascular system. When we extract the digital boundary of this binary image, we keep only the big enough components (say a size greater than 2000).

6. **Fill inside main boundaries** It suffices now to fill the interior of these components, and we get the image of the pulmonary vascular system.

## Morphological filtering

As a starter, we write two classical morphological 3d filters, dilation and erosion.

:::info

Given a neighborhood $N$ (called *structural element*), the **dilation** of an image at some voxel $v$ is the maximum of all values within the neighborhood $N(v)$. The **erosion** of an image is the minimum of all values. These operations respect the structure of an image, in the sense that they keep the order of isolines.

:::

Complete the functions `makeDilation` and `makeErosion` to write these image filters. For the neighborhood $N$, just pick the voxel plus its six direct neighbors (two along each axis).

:::warning

:::spoiler

You can iterate over the points of a domain $D$ using `for (auto p : D)`. You can access the value of an image `image` with `image(p)` or `image.getValue(p)`, and change its value using `image->setValue(p, ...)`. Pay also attention to voxels on the boundary of the domain, whose neighborhood is restricted.

:::

| After 4 dilations | After 4 erosions |

| ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- | ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- |

|  |  |

| Threshold 200 (view 1) | Threshold 200 (view 2) |

|  |  |

## Extract connected components of digital surfaces

The digital surface that is the boundary of a thresholded image is generally not connected. We split it into its connected components, and sort them by decreasing size.

Although you could compute manually connected components using your prefered traversal algorithm or union-find, the job is already done in module [Shortcuts](https://dgtal-team.github.io/doc-nightly/moduleShortcuts.html). The useful method is

```

auto vec_surfs = SH3::makeLightDigitalSurfaces( binary_image, K, params );

```

which returns the vector of (pointers to) connected digital surfaces.

Update function `extractDigitalSurface` to do this job. You must also sort this vector in decreasing order of sizes. Finally, you must keep only the connected components that have a size greater than `minimum_size`. At the end, you must can register each remaining digital surface into polyscope.

:::warning

:::spoiler

`vec_surfs` is a vector of smart pointers to `LightDigitalSurface`s. You can sort them using `std::sort` and a comparator (typically a lambda `[] ( const auto& s1, const auto& s2) { return s1->size() > s2->size(); }`).

For registering the surfaces to polyscope, you can register each of them into polyscope using the same code, just changing its label:

```

std::vector<std::vector<size_t>> faces;

for( size_t face= 0 ; face < primalSurface->nbFaces(); ++face )

faces.push_back( primalSurface->incidentVertices( face ) );

std::vector<RealPoint> positions = primalSurface->positions();

auto primalSurf = polyscope::registerSurfaceMesh

( "Digital surface " + label, positions, faces);

```

Another is to register only one surface, by gathering all the positions and the faces of every connected components into vectors `positions` and `faces`.

:::

## Fill inside lungs

At a threshold between 50-90 (we took 80 here), the largest connected component is precisely the boundary of the lungs and trachea. We design an algorithm that extracts the interior voxels of a given surface, in order to get a binary image representing the pulmonary system.

:::info

It is surprising at first that the largest connected component is inside the body, and not the skin for instance, but this is due to the pulmonary bronchial tree, which is quite ramified.

:::

We proceed following these steps:

1. When extracting the digital surface, you store in global variable `main_surface` the first connected component. You can get all its surfels (i.e. oriented quads) with `SH3::getSurfelRange`. These surfels are passed to `fillSurface` function when clicking on "Fill main surf".

2. To initiate the filling algorithm, for each input surfel `s`, we compute the coordinates of its inner and outer voxels. We queue inner voxels. In image `output`, we set to 1 the outer voxels and to 255 the inner voxels. This creates an impassable wall for the filling algorithm.

3. While the queue is not empty, we retrieve its front voxel, and for each of its valid 6-neighbor (in domain and of value 0 in `output`), we queue it and set its value to 255.

The resulting image is put in variable `lung_image`, whose image can be displayed by setting the corresponding radio button.

:::warning

:::spoiler

* The cellular space `K` provides all the methods to compute voxels from surfels.

```cpp

auto k = K.sOrthDir( s ); // the only direction orthogonal to the surfel

bool b = K.sDirect( s, k ); // the orientation along axis k to reach the positive incident face (so a voxel here)

auto int_voxel = K.sIncident( s, k, b ); // interior voxel

auto int_p = K.sCoords( int_voxel ); // its coordinates

```

* The parameter `inverse` of `fillSurface` is used to reverse the inside/out of the input surface. When 'true', you must reverse the meaning of interior and exterior voxel in `fillSurface`. It should be used here for the lungs, since the exterior of the main digital surface corresponds to the inside of the lungs.

:::

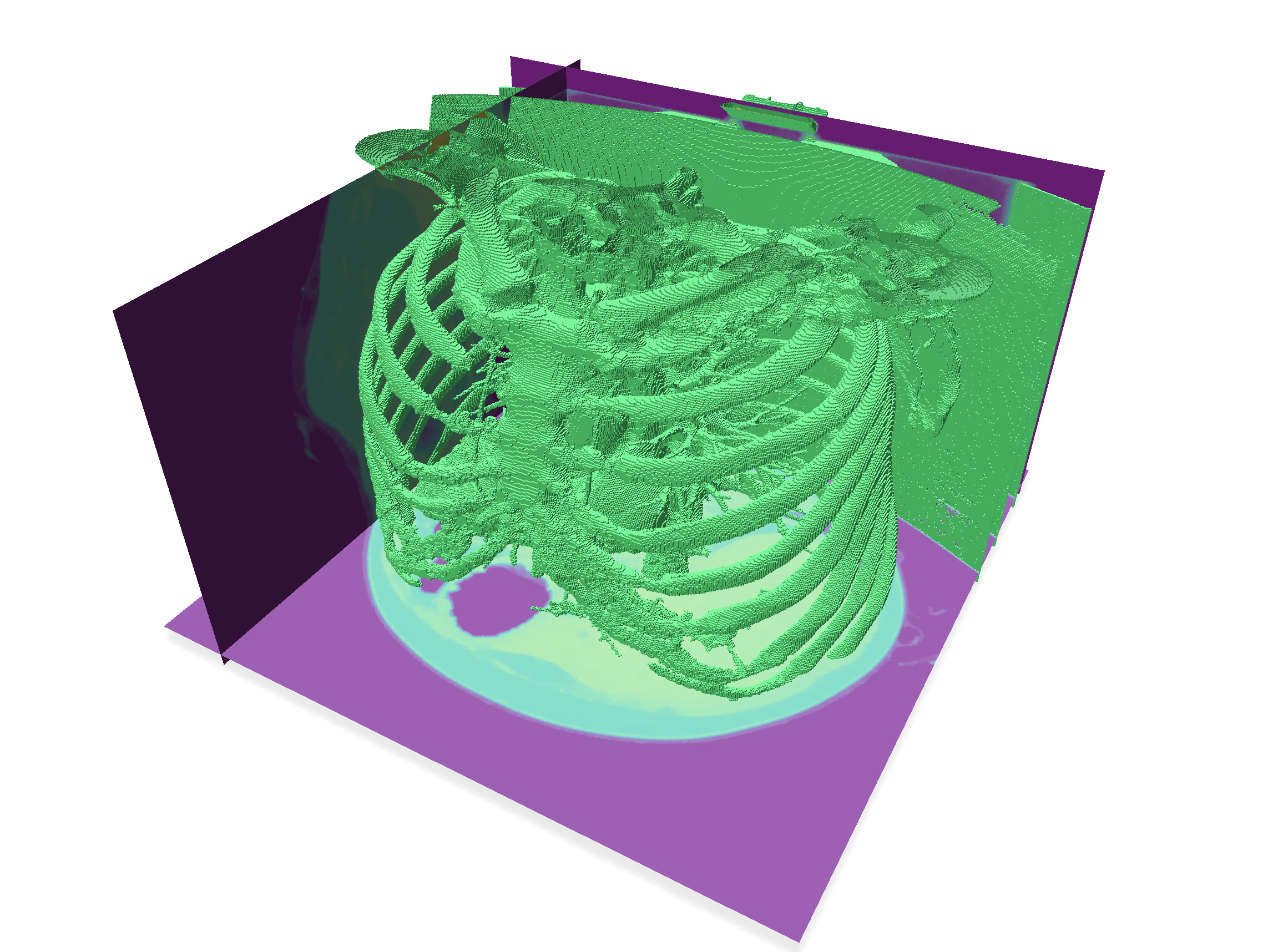

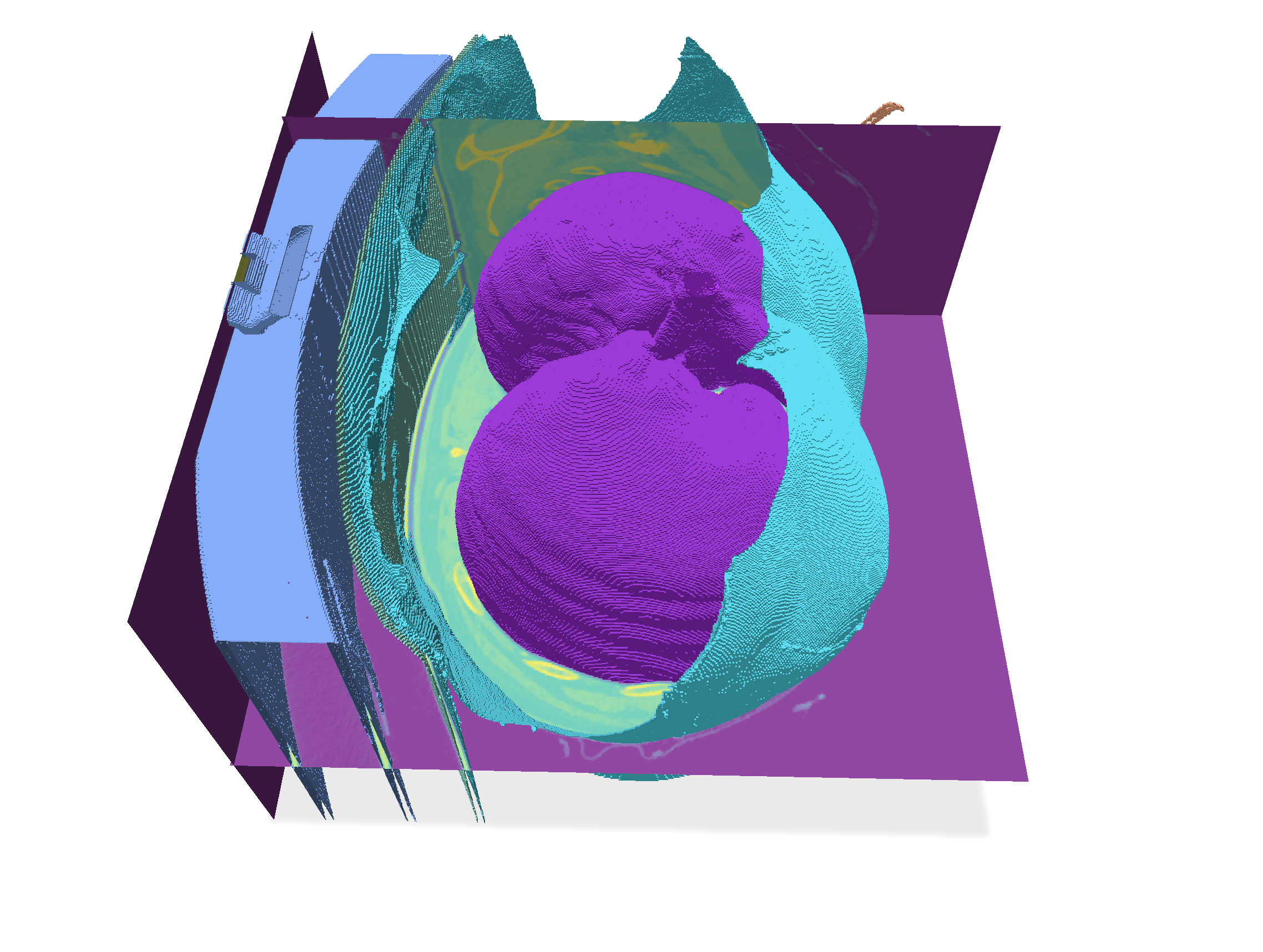

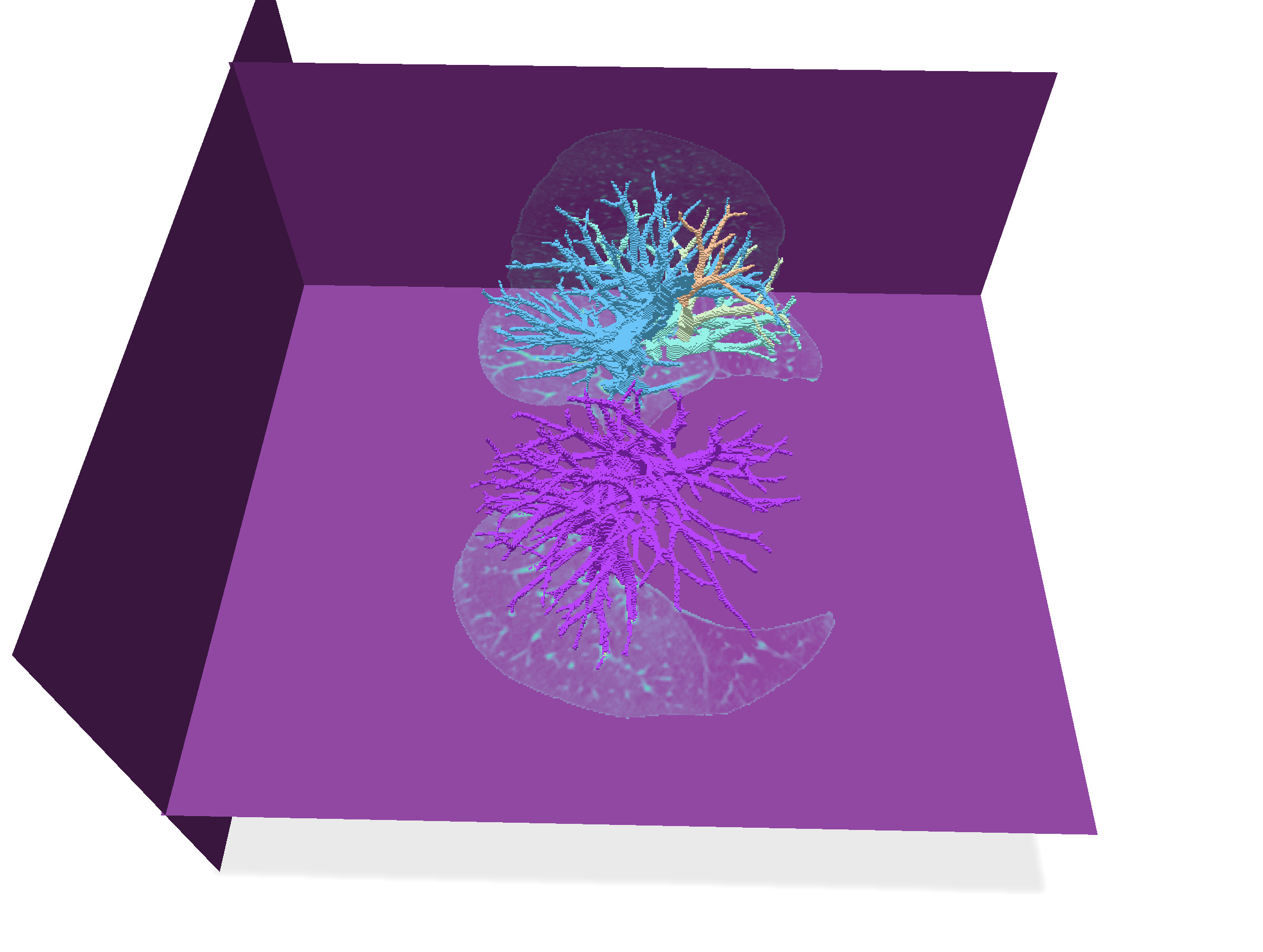

| Input surfaces | After filling main surface |

| -------- | -------- |

|  |  |

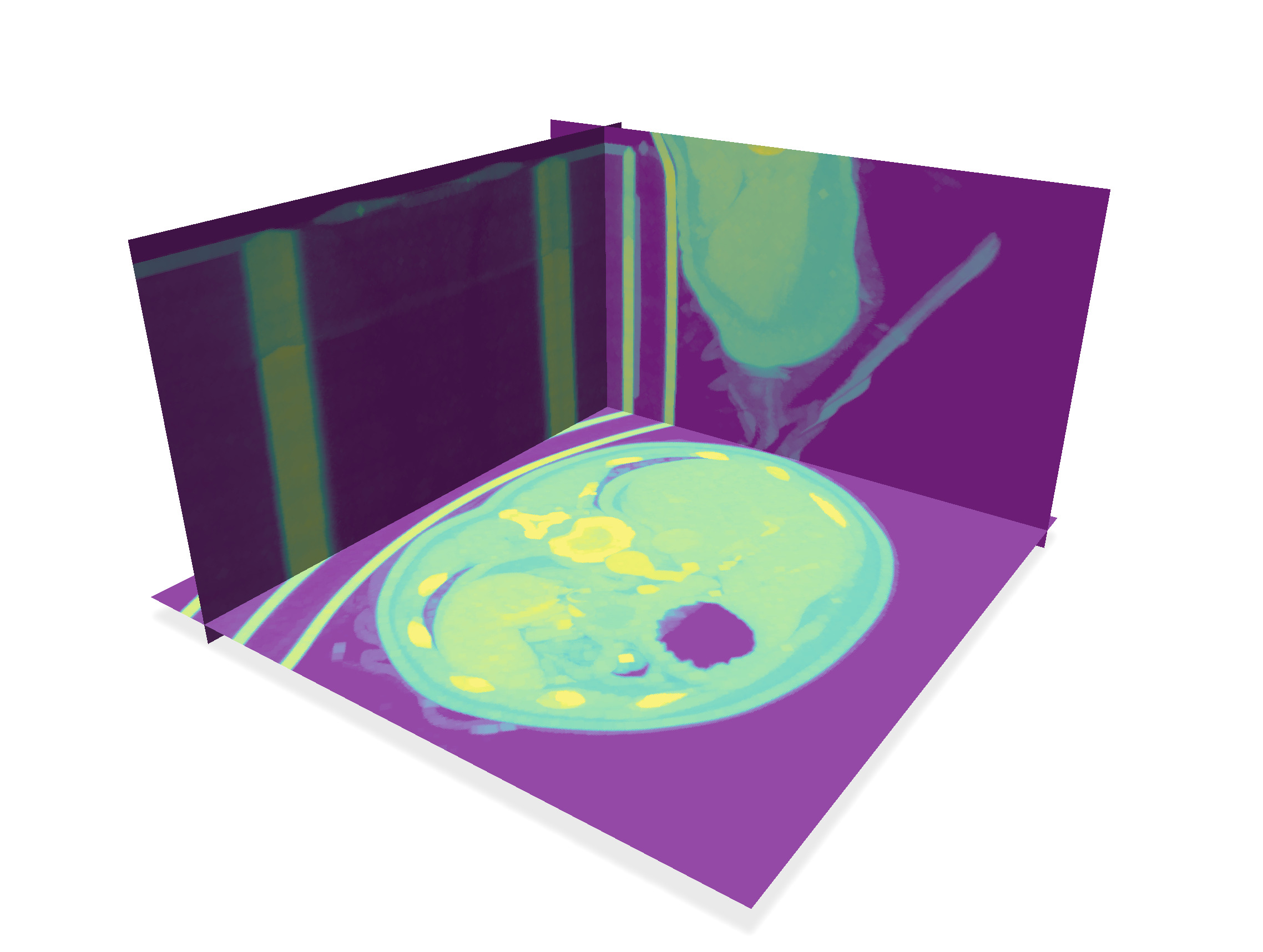

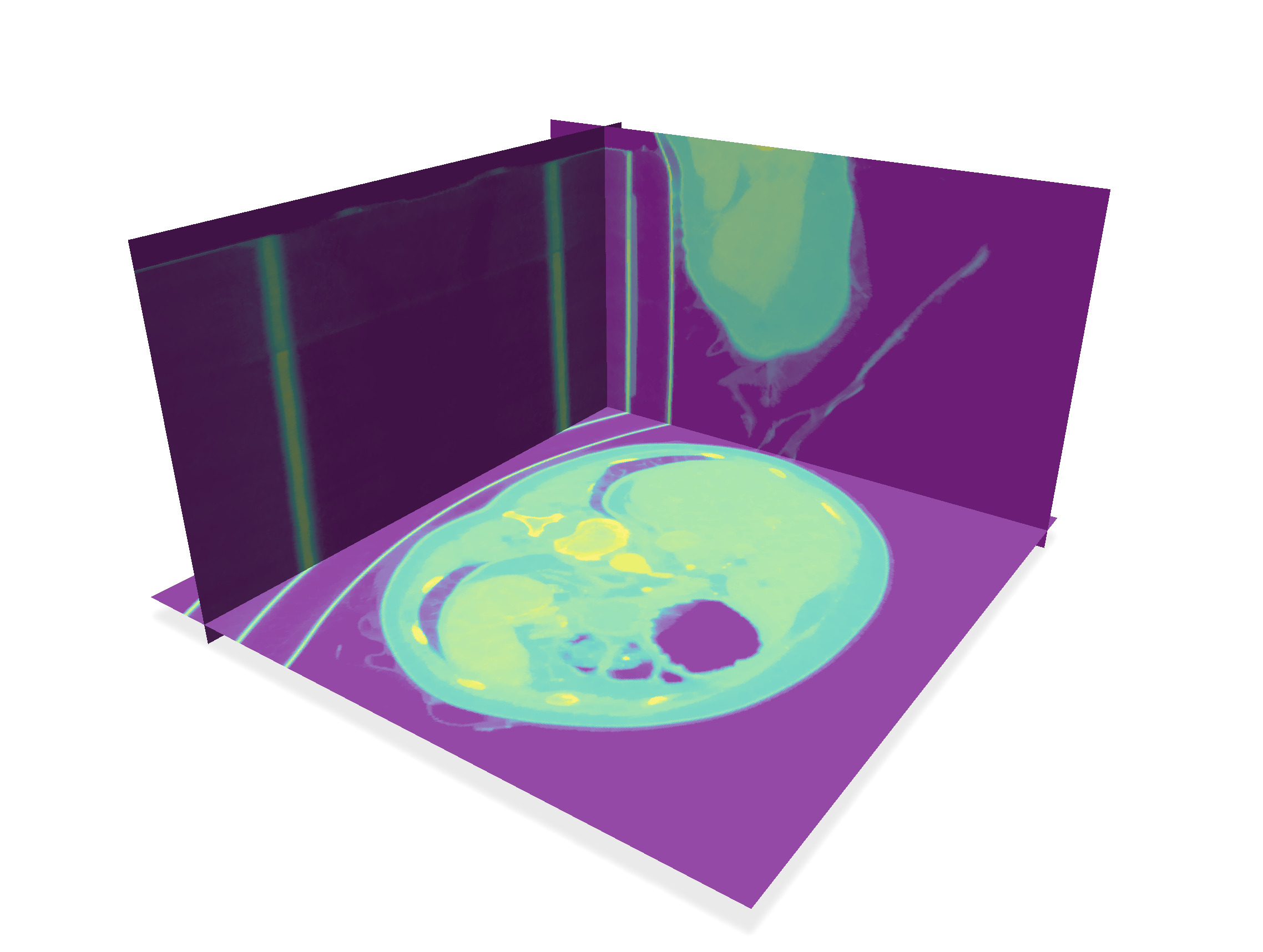

## Select lungs from original image

We eliminate all the complex bronchial and artery system within the lungs using the morphological filters. Then we use this binary image of lungs to select them in the original image, this removing all the other bright parts of the image.

It suffices to do a morphological **closing** operation on `lung_image` with a big enough structuring element. This is done through $N$ **dilations** followed by $N$ **erosions**. Here $N=5$ is enough for low resolution images `PA*-img-low.vol`, while $N=10$ is fine for high resolution images `PA*-img.vol`.

Then this binary image represents the lungs without its complex bronchial system. It remains just to filter the `input_image` by keeping only its part where `lung_image` is 255, and setting to 0 everywhere else. Update the reaction to "Select lungs" button with these operations.

| After 10 dilations then 10 erosions | Updated input image |

| ----------------------------------- | ------------------- |

|  |  |

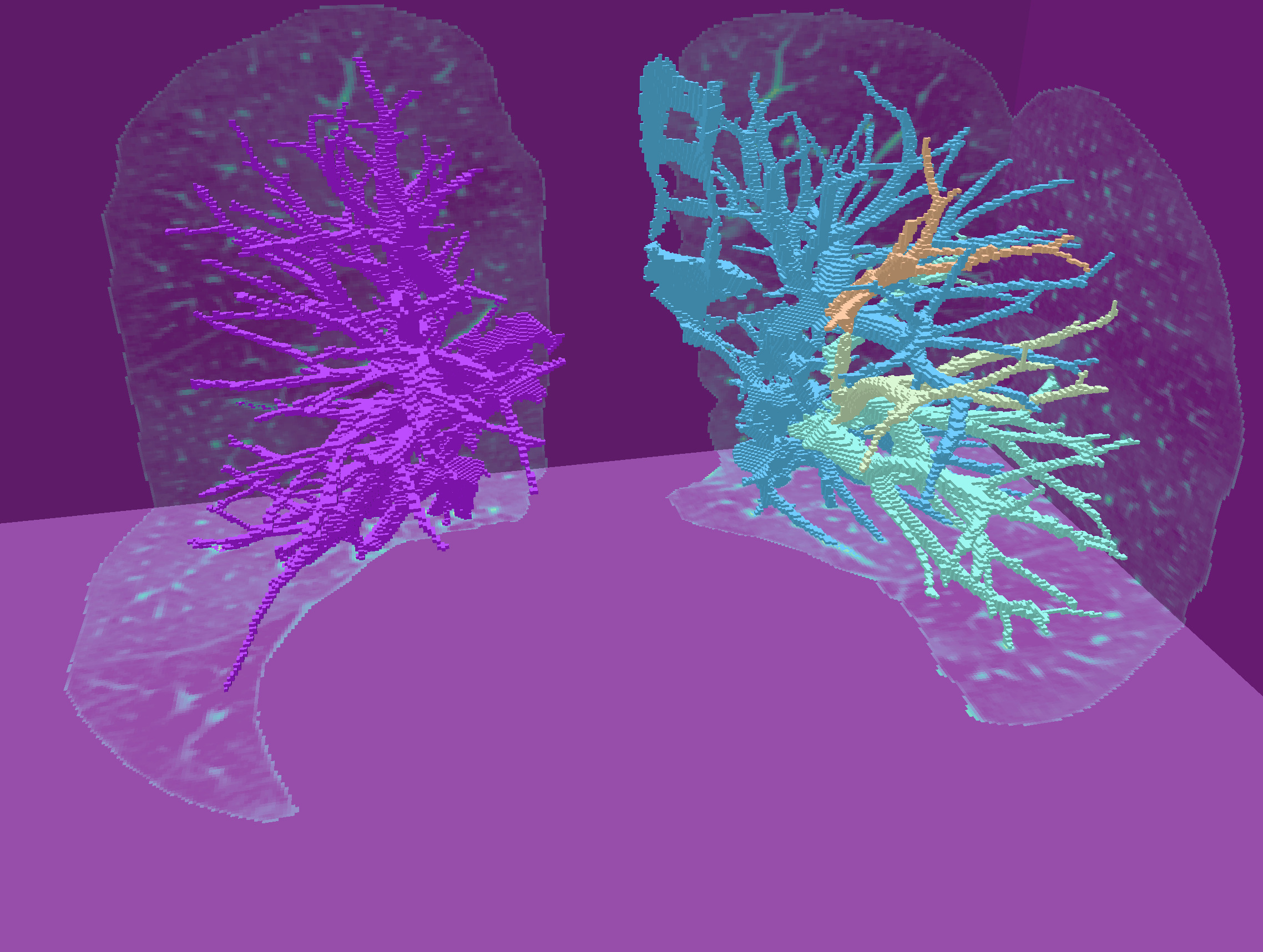

## Extract boundaries of vascular system

We can now threshold the resulting image (approx. 150) to get the pulmonary vascular system. When we extract the digital boundary of this binary image, we keep only the big enough components (say a size greater than 2000).

:::success

You have already written all this part ! Just adjust thresholds `threshold` and `mininmum_size` and extract digital surface.

:::

## Fill inside main boundaries

It suffices now to fill the interior of these components, and we get the image of the pulmonary vascular system.

In the callback to "Fill all surf", just call `fillInterior` on the vector gathering all the surfels of each connected component.

:::warning

:::spoiler

Just compute the vector `all_surfels` in function `extractDigitalSurface` while selecting the big enough components: if the component is big enough, you add its surfels to `all_surfels`, otherwise you stop.

:::

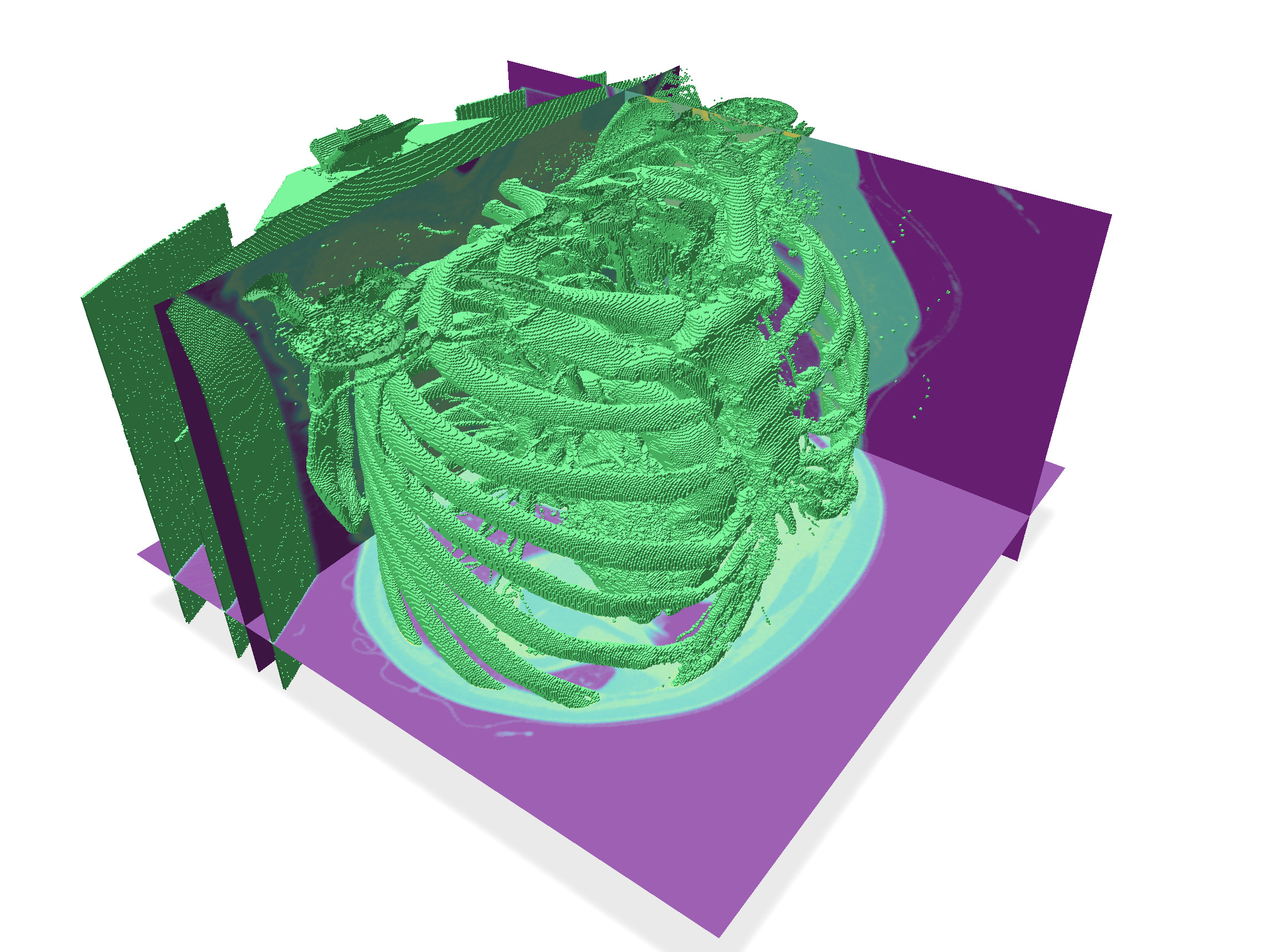

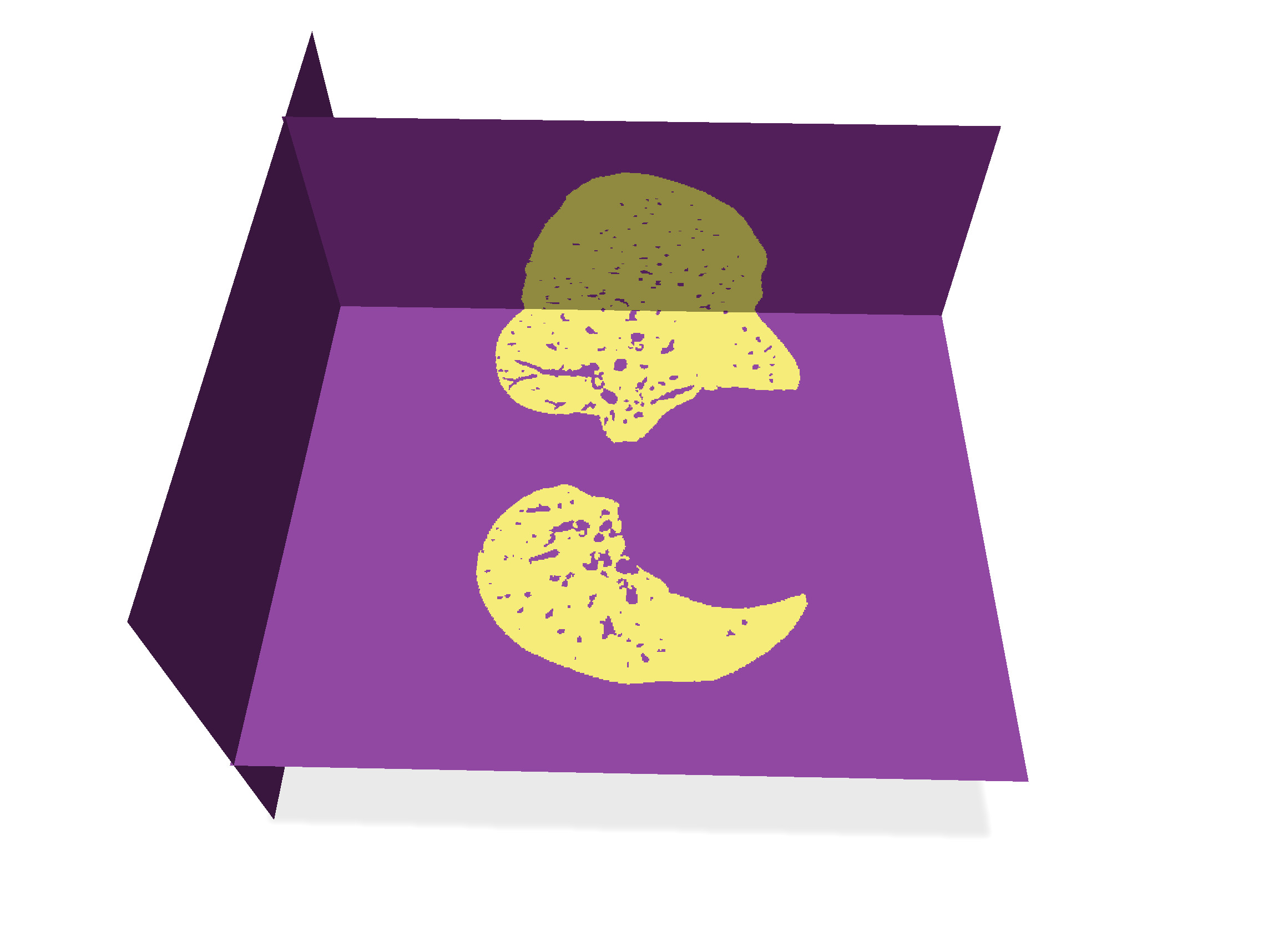

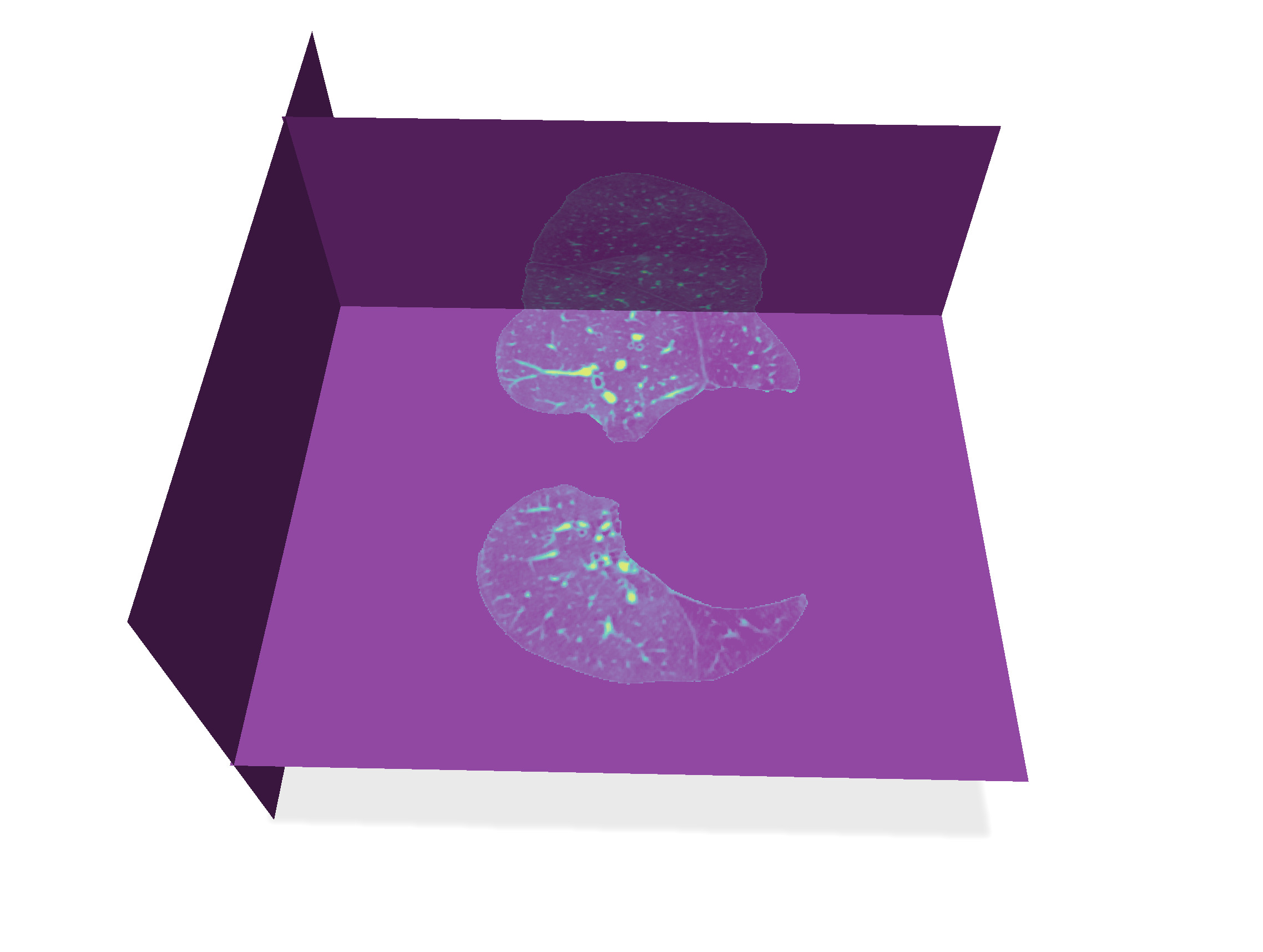

| Digital surfaces | Their interior voxels |

| ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ | ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ |

|  |  |

|  |  |

You can save the resulting images with "Save vol", and compare your results to manually segmented images `PA*-lbl.vol` and `PA*-lbl-low.vol` .

:::success

That's all folks !

:::

## References

[^1]: G. Luo, K. Wang, J. Liu, S. Li, X. Liang, X. Li, S. Gan, W. Wang, S. Dong, W. Wang, P. Yu, E. Liu, H. Wei, N. Wang, J. Guo, H. Li, Z. Zhang, Z. Zhao, N. Gao, N. An, A. Pakzad, B. Rangelov, J. Dou, S. Tian, Z. Liu, Y. Wang, A. Sivalingam, K. Punithakumar, Z. Qiu and X. Gao (2023). Efficient automatic segmentation for multi-level pulmonary arteries: The PARSE challenge. ArXiv, abs/2304.03708. [ArXiv](https://arxiv.org/abs/2304.03708)

[^2]: Chu, Y., Luo, G., Zhou, L. et al. Deep learning-driven pulmonary artery and vein segmentation reveals demography-associated vasculature anatomical differences. Nat Commun 16, 2262 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56505-6. [Link](https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-025-56505-6)